CNN’s Chevy Chase documentary offers honesty and discomfort, asking viewers to decide whether understanding a star excuses his worst behavior.

Marina Zenovich’s new CNN documentary, I’m Chevy Chase and You’re Not, doesn’t try to rescue its subject’s reputation, but it also doesn’t tear it down.

Instead, it sits in an uncomfortable middle space, asking viewers to wrestle with a question Hollywood has avoided for decades: what do we do with talented people who are difficult, hurtful, and still deeply human?

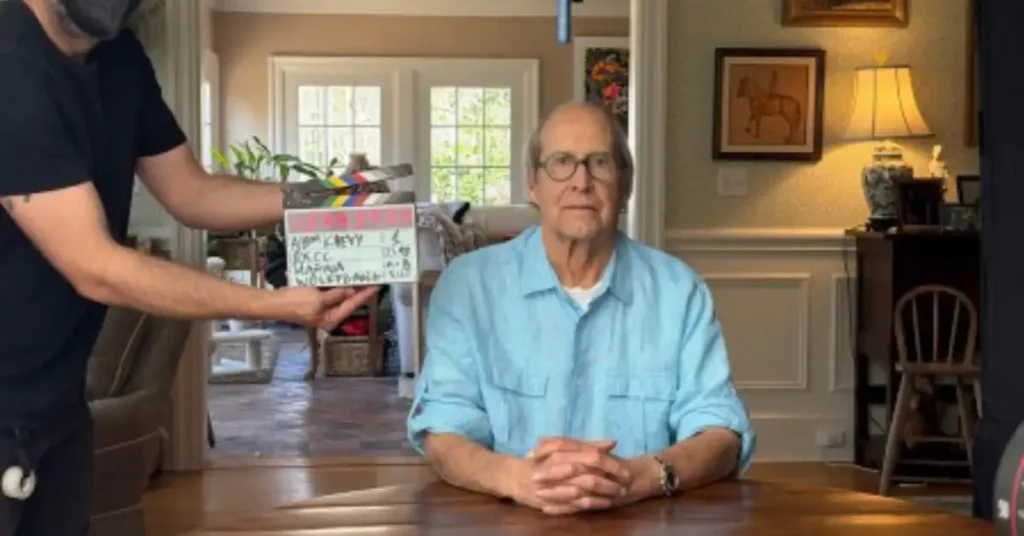

From the opening moments, the film makes one thing clear — Chevy Chase is not here to apologize, perform a redemption arc, or neatly explain himself. At 82, the comedy legend is present, engaged, and often combative. He agrees to participate, yet seems irritated by the very act of being examined. That tension becomes the backbone of the documentary.

Zenovich, known for portraits of controversial figures like Lance Armstrong and Roman Polanski, approaches Chase in a similar way. She listens, observes, and documents contradictions rather than forcing conclusions. The result is a film that reveals a lot, but resolves very little.

Rather than framing Chase as either a misunderstood genius or an irredeemable bully, the documentary presents him as something messier: a man whose career soared on confidence, ego, and timing — and later crashed under the weight of the same traits.

The story of Chase’s rise is familiar but still striking. From his early days as a college musician to becoming one of the original breakout stars of Saturday Night Live, Chase’s charm and physical comedy made him instantly famous. His Weekend Update line, “I’m Chevy Chase and you’re not,” captured both the joke and the truth behind it. Confidence wasn’t just part of his act — it was his armor.

The documentary traces how that armor hardened over time. Leaving SNL early, becoming a major movie star, and then burning bridges across sets and studios are well-worn chapters in Chase’s history. Zenovich doesn’t shy away from describing him as cruel, insensitive, and frequently unpleasant to work with. In fact, Chase himself often proves the point.

When Zenovich presses him on difficult topics, Chase responds with sarcasm, deflection, or performance. He mocks her intelligence, dodges accountability, and sometimes refuses to engage at all. These moments aren’t playful banter — they feel like a wall going up. Unlike documentaries where tension between filmmaker and subject becomes productive, here it often feels like a stalemate.

That’s why the film leans heavily on others to fill in the gaps. Friends, family members, colleagues, and industry figures help shape the larger picture. His brothers and college friends describe his early life. SNL veterans like Lorne Michaels and Dan Aykroyd reflect on his groundbreaking impact. Former co-stars and collaborators discuss his work, his talent, and his volatility.

Yet the absences are just as loud as the voices included. Key figures connected to Chase’s most controversial moments are missing, leaving some stories feeling incomplete. Instead of firsthand accounts, the documentary often relies on secondhand retellings or written histories, which limits how deeply it can explore harm and accountability.

Where the film becomes most affecting is not in the recitation of scandals, but in its quieter moments. Zenovich captures Chase at home in Bedford, New York, living a relatively calm life with his wife and family. We see him interacting warmly with fans at Christmas Vacation Q&A events, cracking jokes, smiling, and seeming genuinely grateful.

In these scenes, Chase feels approachable, even likable. They complicate the image of the “difficult” man and suggest that people can be very different depending on where — and with whom — they are.

Late in the documentary, Zenovich introduces the most headline-grabbing revelations: Chase’s childhood abuse, a devastating career crash after his talk show was canceled, an eight-day coma following heart failure, and memory loss that may affect his ability to recall past events. These details are undeniably sad, and they invite empathy.

But the film stops short of clearly connecting those experiences to Chase’s harmful behavior. Instead, they hover in the background, offering context without explanation. Viewers are left to decide whether understanding pain should soften judgment — or whether it simply explains how damage continues to spread.

This approach raises difficult ethical questions. If Chase genuinely cannot remember certain incidents, what does it mean to ask him to answer for them now? Does that absolve him, or does it merely shift the burden of reckoning onto the audience?

The documentary also avoids placing enough responsibility on the institutions that enabled Chase’s behavior for decades. Hollywood rewarded his talent repeatedly, even after patterns of misconduct were well known. Studio executives, network leaders, and powerful producers are largely spared serious scrutiny. Their complicity is implied, but rarely examined.

That omission feels like a missed opportunity. Chase didn’t exist in a vacuum. He worked in an industry that often tolerated bad behavior as long as the results were profitable. Without addressing that system directly, the documentary risks making Chase seem like a singular problem rather than part of a larger one.

By the end, I’m Chevy Chase and You’re Not doesn’t offer closure. It doesn’t ask viewers to forgive, forget, or condemn. Instead, it asks something harder: to sit with contradiction. Chase emerges as a man capable of warmth and harm, humor and cruelty, love and arrogance — sometimes at the same time.

The title, once a punchline, takes on a quieter sadness here. Being Chevy Chase brought fame, success, and laughter to millions. It also brought isolation, resentment, and regret. Whether that trade-off was worth it is a question Zenovich leaves unanswered — and perhaps can’t be answered at all.

In that sense, the documentary succeeds not by explaining Chevy Chase, but by showing why he remains so difficult to explain.